6.4. Causality#

Here is a recap of the three criteria for establishing causality (you saw these in Week 6 last term, “Regression Models, Multivariate Analysis”).

The three criteria for causation are:

Association between the variables, where we must show that \(x\) and \(y\) are associated, i.e., if \(x \rightarrow y\), then as \(x\) changes, the distribution of \(y\) should change in some way.

An appropriate time order: the two variables have the appropriate time order, with the cause preceding the effect.

The elimination of alternative explanations: when two variables are associated and have the proper time order to satisfy a casual relation, this is still insufficient to imply causality. The association may have an alternative explanation, such as a confounding factor on which we have no information.

How do experiments help to establish causality?

Click to reveal answer

Experiments help us with the time ordering, since we measure the outcome after the intervention/ manipulation. But more importantly, they help to rule out alternative explanations. Since any confounding factors (whether measured or not!) should be equally distributed between the control group and the treatment group, any differences after the intervention must be because of the intervention.

When analysing experimental data, do you need control variables?

Click to reveal answer

No. In principle, we do not need any control variable because of the random assignment into treatment and control conditions. (In practice, it is not uncommon to see some basic controls in the analysis of experiments). Controls variables are usually more important with observational data, as there is a greater need to rule out alternative explanations.

Example: alcohol consumption and health

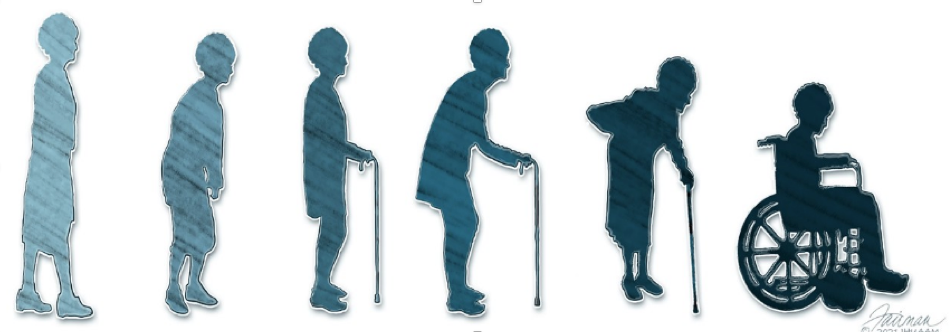

In a research project about healthy ageing, the research team had to interpret the outcome of the regression table below. The outcome variable is “frailty”, a commonly used measure of functional health among older people, where higher scores indicate higher frailty. One explanatory variable for health behaviours was a categorical variable of alcohol consumption. The reference category (omitted from the table) is “drinking alcohol daily or almost daily”.

Dep. Variable: Frailty

Model: OLS

No. Observations: 10,520

Coef |

srd err |

P>[t] |

|

|---|---|---|---|

Intercept |

-6.567 |

0.448 |

0.000 |

Age |

0.350 |

0.006 |

0.000 |

Income |

-1.064 |

0.038 |

0.000 |

Education: degree |

-3.799 |

0.163 |

0.000 |

Alcohol |

|||

Once or twice a week |

-0.271 |

0.120 |

0.024 |

Once or twice a month |

0.896 |

0.165 |

0.000 |

Special occasions only |

1.929 |

0.146 |

0.000 |

Not at all |

5.596 |

0.180 |

0.000 |

Given that we are usually told that drinking alcohol is bad for our health, what is surprising about the result?

Click to reveal answer

People who drink once or twice per week are less frail than people who drink every day which is probably what we would expect to see. However, the people who drink more rarely, such as only once or twice a month, on special occasions, or not at all, are MORE frail than people who drink every day.

And, how do you think we can explain this surprising result?

Click to reveal answer

This could be an example of a “selection effect”. It is possible that people who are ill – perhaps with a diagnosis of a disease – have been advised by their doctor to stop drinking alcohol. In this case the more ill people are the ones that do not drink much alcohol, but the non-drinking did not cause their poor health.