18.3. Research Design Concepts#

What do the following three concepts mean, in the context of conducting experiments? Manipulation, Control, and Random Assignment

Click to reveal answer

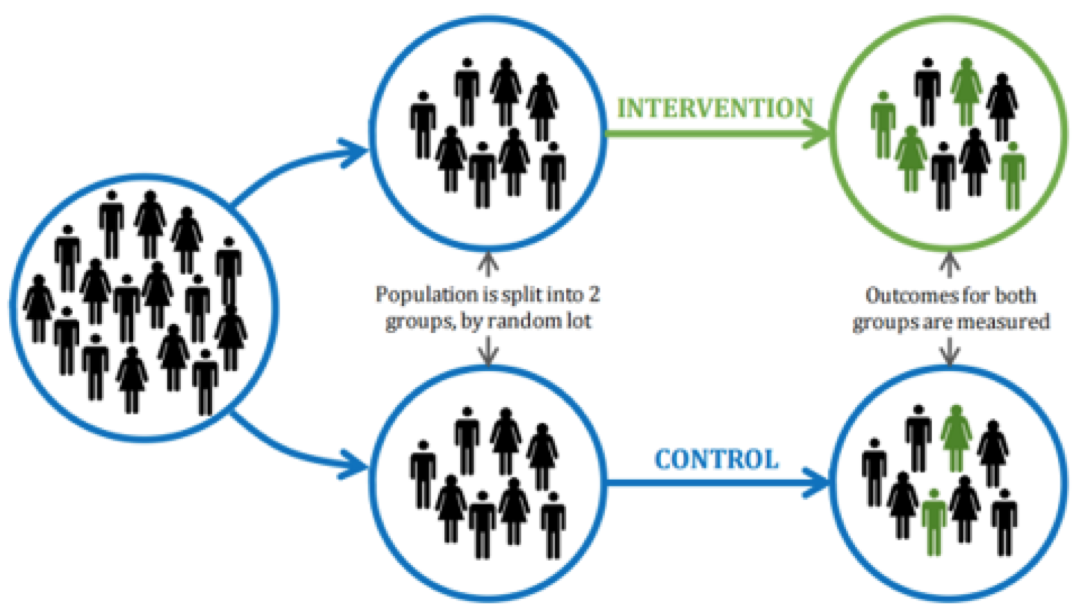

Manipulation: to test relationships, the experimenter deliberately introduces change in an independent variable (i.e., the treatment), and then observes the effects of this change

Control: the experimenter controls which unit will receive treatment, and experimenters often have the ability to control the conditions of observation.

Random Assignment: subjects are randomly assigned to treatment and control groups; besides the receipt of a treatment, these two groups are equivalent.

What is the point of randomization?

Click to reveal answer

Random assignment helps to control for any pre-existing differences between groups. If we assign to treatment and control groups randomly, all potentially-confounding characteristics should be evenly distributed between groups. For example, there should be no differences in the average health, or the average level of liberal views between treatment and control group.

Why do we need a control group? Why not just compare the outcome before and after manipulation?

Click to reveal answer

Because change may occur that is not related to the treatment such as natural fluctuations or regression to the mean. If there is a significant difference between treatment and control groups after the intervention, we know that the difference is unrelated to any changes over time that affected both groups.

What is the difference between observational data and an experiment?

Click to reveal answer

Observational data are where the researcher does not ‘intervene’ in any way; they simply measure and record what they observe. An example would be doing a survey, where for example you could ask people about their exam test scores and their coffee-drinking habits. In contrast, in an experiment, the researcher manipulates the experience of the study participants in some way, and this manipulation becomes the explanatory variable of interest. For example, in a lab experiment some people could be given coffee, and some given water, before measuring their performance on a test.

The problem with the observational study is that we only observe one outcome per person. We know the test scores of the people who report being a coffee drinker, but what if people who are highly motivated and ambitious try harder in tests AND drink more coffee so they can study longer? There may be an association and no causality. In the observational study, we do not observe the counterfactual. In an experiment, we mimic the counterfactual by having a control group to which people are randomly assigned.

Example: A researcher working in an organisation wishes to understand whether a training course on equal opportunities and diversity raises the level of concern about the gender pay gap.

Spend a couple of minutes thinking about two possible study designs to address the question: one observational study and one experimental study. How can we infer causality in each case?

Click to reveal answer

A possible answer would be study 1: a company survey. The employees of the organisation are surveyed, using a random sample if it is a large company, and with attention to getting a good response rate. The survey would collect information on whether the employee has taken the training course or not, and on their level of concern about the gender pay gap. The problem with this study design is that we do not know whether it is the most concerned employees who opt in (i.e., ‘select in’) to the training, and therefore the survey results cannot reveal if the training causes the concern. The research team could mitigate this to some extent by collecting data on confounding factors such as their gender, education level, and perhaps other liberal attitudes to use as control variables. But even with control variables, we couldn’t be completely sure that the association between the training and concern level is causal.

Study 2: an experiment. In this case the experiment is set up before anyone in the organisation takes the training. Employees are randomly selected to participate in the study. Of those participating, they are randomly assigned into control and treatment groups. The treatment group are asked to take the equal opportunities training. The control group are asked to take a short training course on a completely unrelated topic such as fire safety. After a one-week window in which the participants have completed their training, they are surveyed to find out about their level of concern about the gender pay gap. The researcher compares the concern level between control and treatment groups using a statistical method such as a $t$-test. If there is a significant difference this is interpreted as a causal effect of the equal opportunities training and the random allocation ruled out any pre-existing differences between the two groups.

Do experiments always take place in a lab?

Click to reveal answer

No! Experiments can be online, or ‘in the field’, or in a laboratory or clinical setting. The key design elements in an experiment are manipulation and random assignment. Wherever/ however you do the research, it is these elements – rather than the place – that define it as an experiment.

In what kind of research scenarios are experiments not possible?

Click to reveal answer

There are two main reasons an experiment is not possible: ethics and resources. We cannot randomly assign people to poverty to see what happens to them, and we couldn’t choose not to treat an ill person to see what happens. It would be unethical. Sometimes, research problems are simply too big or resource-heavy to run an experiment. It would be interesting to randomly assign people in over-crowded housing to live in big houses and measure their life improvements. But it would be extremely expensive, and beyond most research budgets.

What is a natural experiment?

Click to reveal answer

Natural experiments arise from naturally occurring phenomena. Here, the manipulation of the treatment is not under the control of the analyst; rather the “natural” intervention approximates the characteristics of a randomized experiment. One example relates to the consequences of Hurricane Katrina, where prisoners could not return to their usual neighbourhoods when released from prison in the months after the hurricane. Would this be a good or bad thing for their chances of staying crime-free and out of prison? Here’s a blog post about it if you want to find out.