2.4. Rank-based tests#

Here we review a class of statistical tests based on replacing data with their ranks.

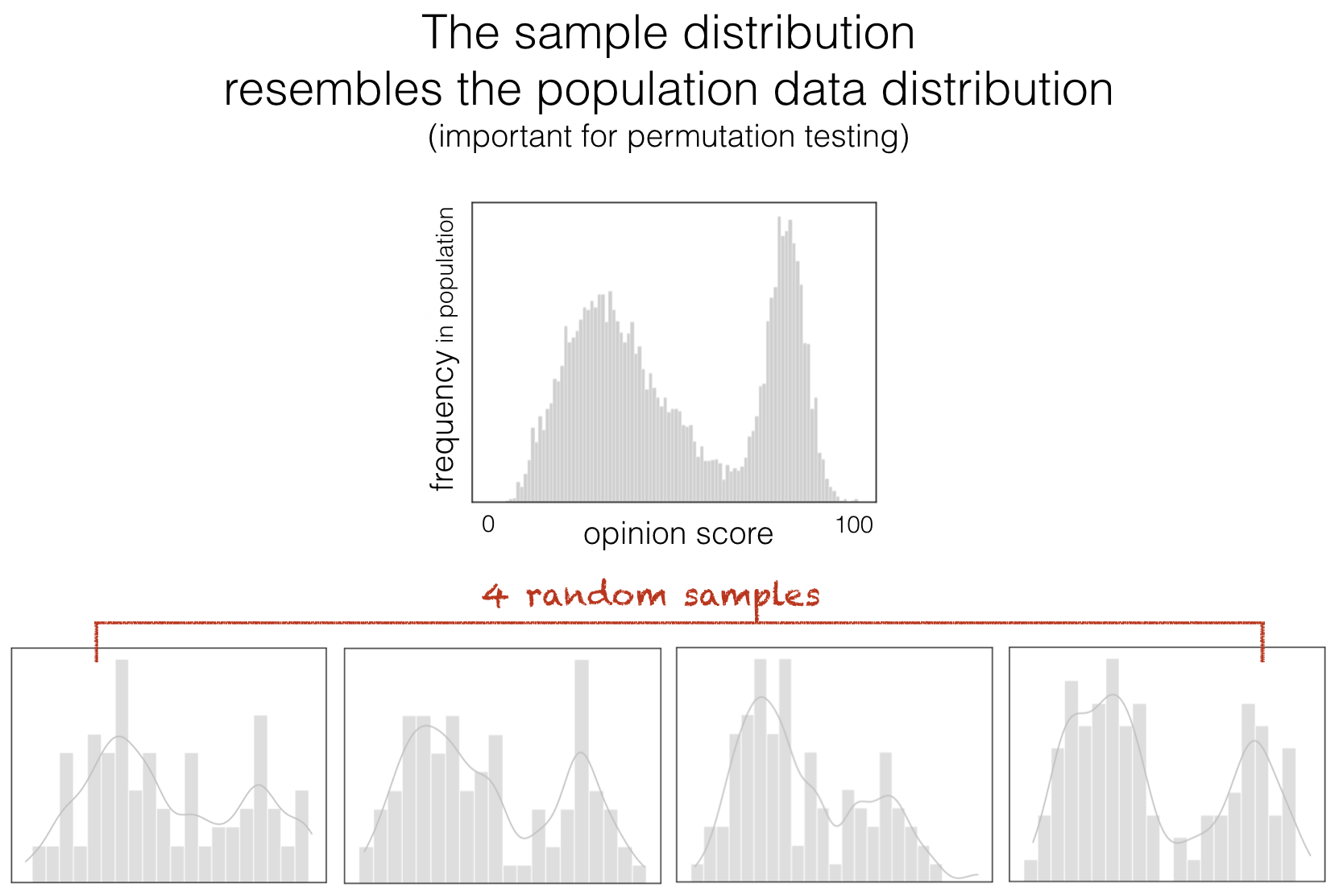

2.4.1. Permutation tests assume the population is similar to the sample#

In general, if we draw a small sample of data from a larger population, the distribution of data within the sample resembles the distribution in the population.

The figure above shows four random samples of 100 individuals from the bimodal distribution above. These are made-up data, but I like to this of them as something like scores out of 100 representing people’s opinions about a polarizing issue, such as how migrants should be treated or whether inheritance tax is fair; people tend to have either high scores or low scores, but not many people have a neutral opinion.

You will see that the data distribution within each sample resembles the original population (having two peaks).

Permutation testing makes use of the fact taht the distribution of data in a small sample can generally be seen as representative of the population as a whole - we shuffle up the sample (disregarding which group people belonged to because we are assuming the null hypothesis is true, and group doesn’t matter). This shuffling process gives us lots of ‘new’ random datasets, we are able to estimate how much the sample mean can move around due to chance. The exact distribution of the sample mean in the shuffled data (the null distribution) will naturally depend on the data distribution itself - in this case we are implicitly assuming that the distribution of the data we are shuffling (the sample) is representative of the population data distribution as a whole.

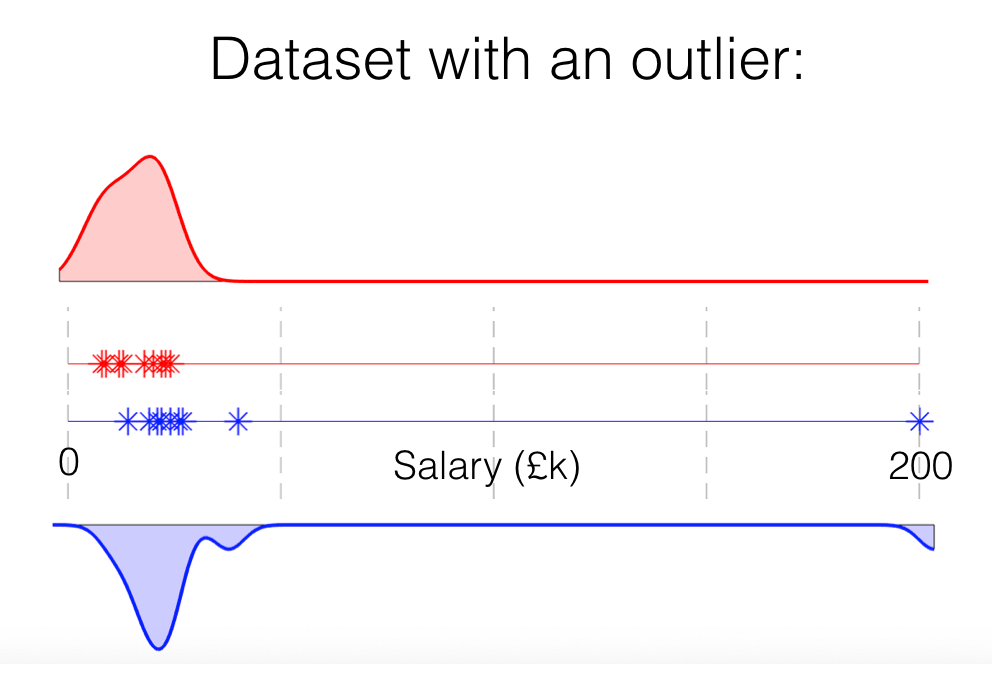

2.4.2. But small samples may not be representative#

When we are working with a sample of data, espcially a small sample, there is always a chance our sample is unrepresentative of the wider population.

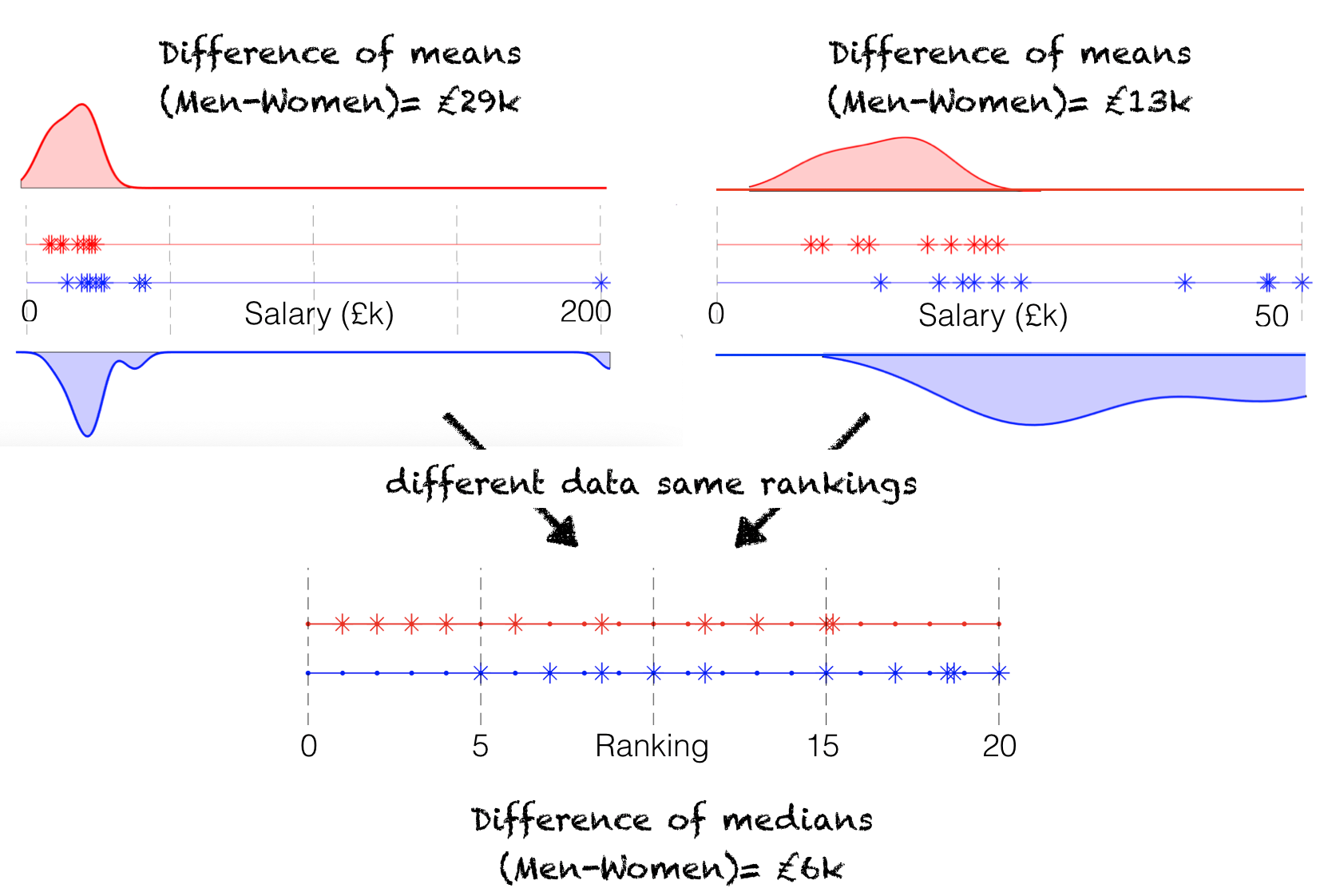

For example, consider these salary data for men and women. There happens to be a huge outlier in the ‘men’ group - someone who earns £200k, whilst everyone else earns less than £50k.

Because there are only 20 people in our sample, if we generalize from this sample to the population (which we implicitly do when running a permutation test), we are accepting that 1/20 people or 5% earn £200k (actually it's more like 1%).

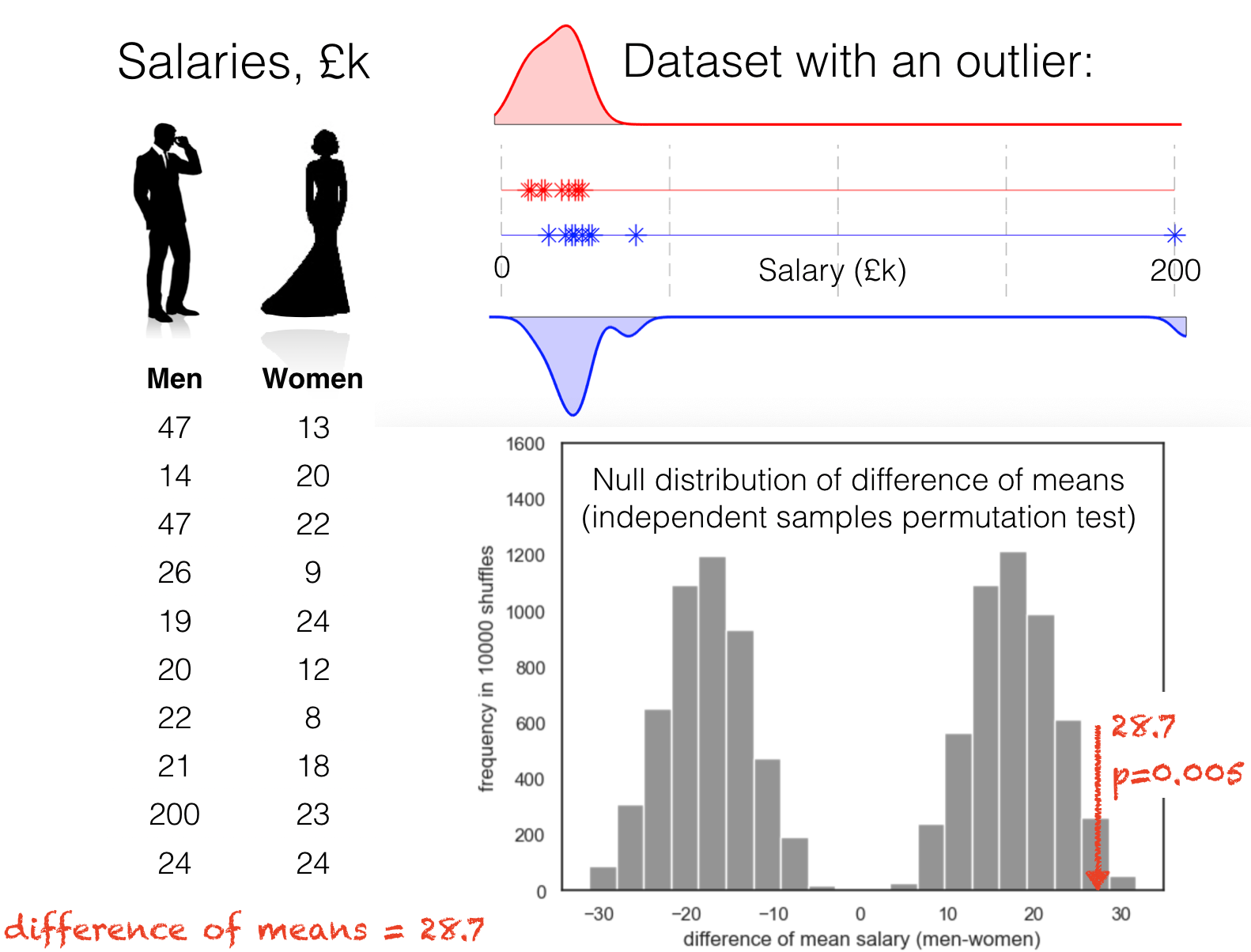

2.4.3. Outliers can have a big effect on our statistical tests#

In permutation testing case, we shuffle up everyone’s salaries and assigning the labels ‘man’ and ‘woman’ randomly. Then we ask how often we get a difference of means as large as the observed value (in this case £28k) in shuffled data - because such difference in shuffled data must be due to chance, this allows us to quantify how likely our observed value would be to arise due to chance.

If we do that we can see that the shuffled difference of means fall into two completely separate groups - cases where the £200k person was labelled as a man, and cases where they were labelled as a woman. Arguably, this means our conclusions depend pretty heavily on the single observation that one man had a very high salary.

Note that such extreme outliers can arise by ‘luck’ (we happen to sample someone atypical), but can also arise from measurement error (for example a noisy measurement from a brain imaging machine) or user error (incorrect data input) as previously discussed (in ‘data wrangling’).

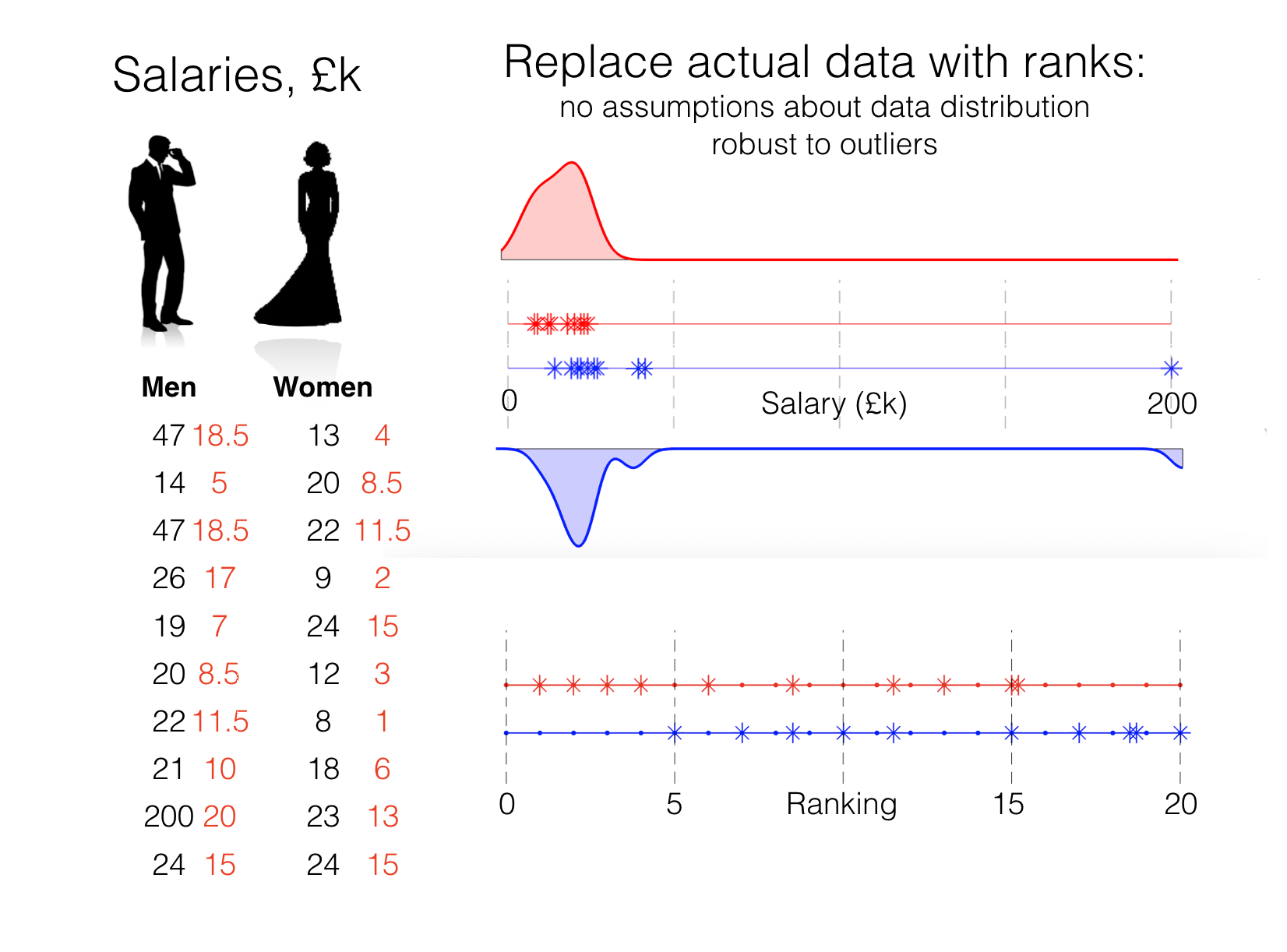

2.4.4. Replacing data with their ranks reduces the effects of outliers#

One way to make our analysis less sensitive to outliers is to work with the ranks of the data, rather than the data themselves. When we rank data, the smallest data value becomes rank 1, the next smallest rank 2, and so on. The largest data value naturally becomes rank \(n\), where \(n\) is the sample size.

Because the largest value is always rank \(n\), no matter its numerical value, ranking the data really reduces the effect of outliers:

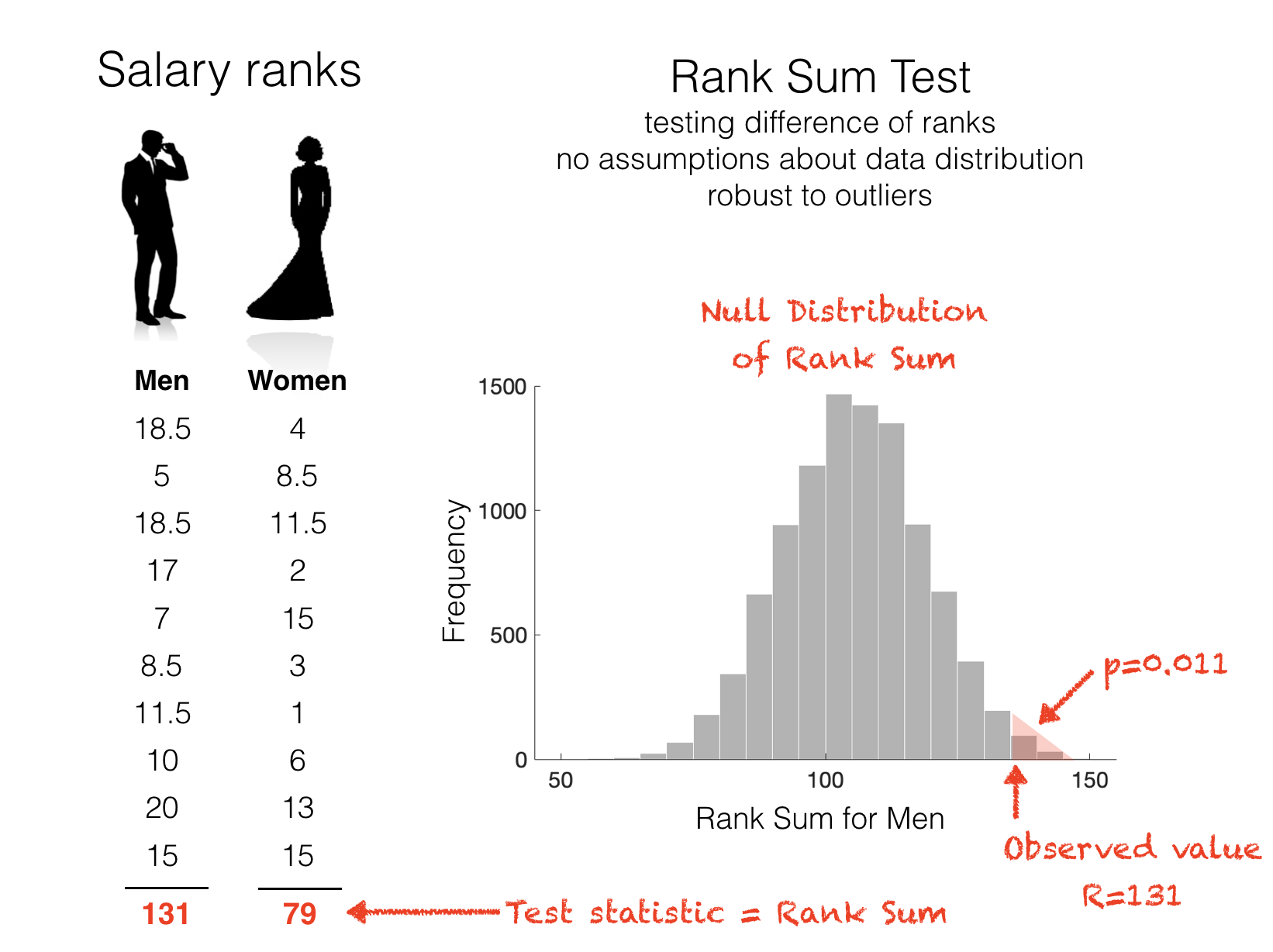

Having converted our data into ranks, we can then ask something about whether the proportion of high ranks falling into one category (and the proportion of low ranks falling into the other category) is greater than we would expect due to chance. In terms of the salary example, the four highest ranked people in the dataset would be men (because the four people with the highest salaries are all men). Overall more of the higher ranks will fall into the ‘men’ group.

We summarize how many of the high ranks ended up in the ‘men’ group by the Rank Sum (see worked example on the next page). The rank sum for our actual data is 131.

2.4.5. Null distribution of the Rank Sum#

Under the null hypothesis, we would expect high- and low ranks to fall equally into the ‘men’ and ‘women’ categories.

We can now generate the null distribution of the rank sum by effectively doing permutations of ranks rather than data

actually the null distribution for ranks can be worked out exactly with an equation which effectively checks all possible permutations of ranks - but we don’t need to delve into that.

2.4.6. Null distribution based on ranks is not so sensitive to the outlier#

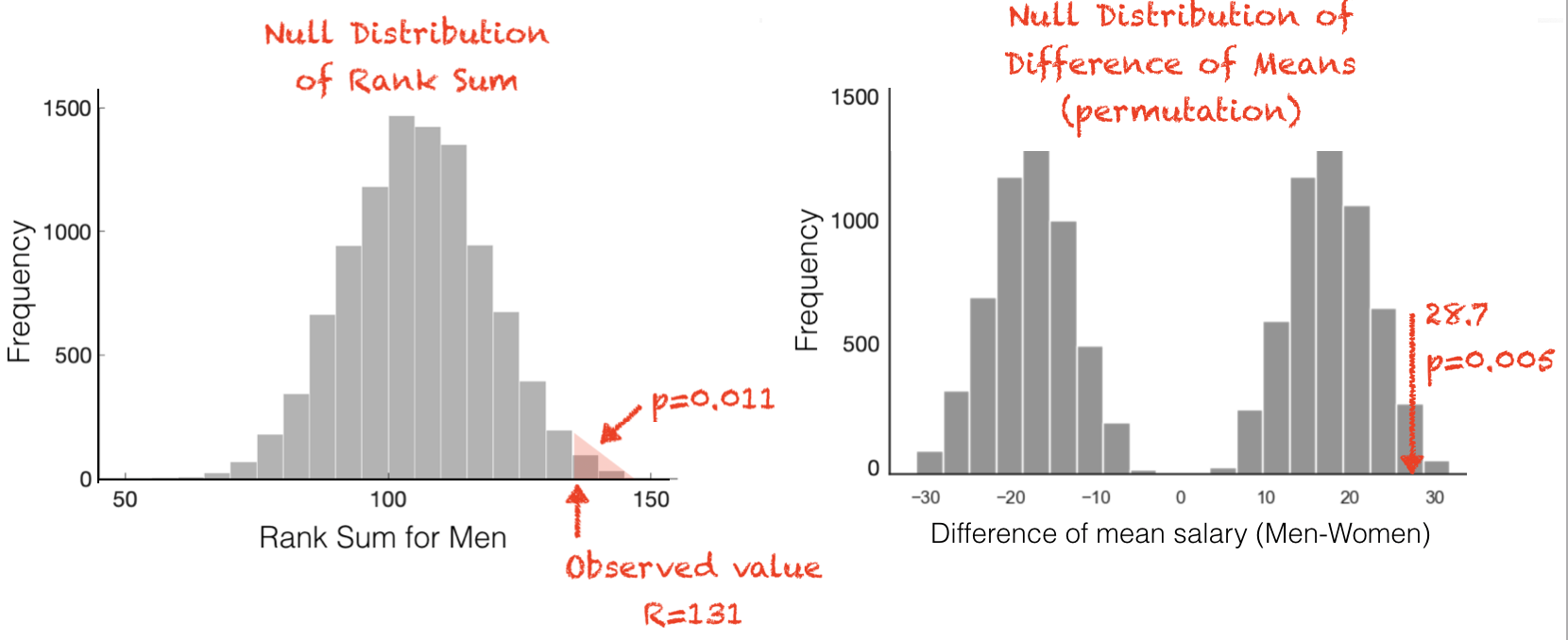

Compare the shape of the null distribution of the rank sum to that of the null distribution of the mean differece.

We can see that the effect of the extreme outlier is much reduced, because we no longer find two peaks in the null distribution, which as you will recall indicated that whether the difference of means favoured men or women depended strongly on whether the extreme outlier, £200k person, was labelled as a man or a woman.

2.4.7. Conclusions#

A test based on ranks is more robust to outliers that a permutation test.

This is because they make different assumptions:

The permutation test implicitly assumes that the sample (including any outliers) is typical of the population.

The rank based test only assumes that the rankings are typical of the population, which is a weaker assumption.